Archive for July, 2010

On exhibit

Friday, July 9th, 2010

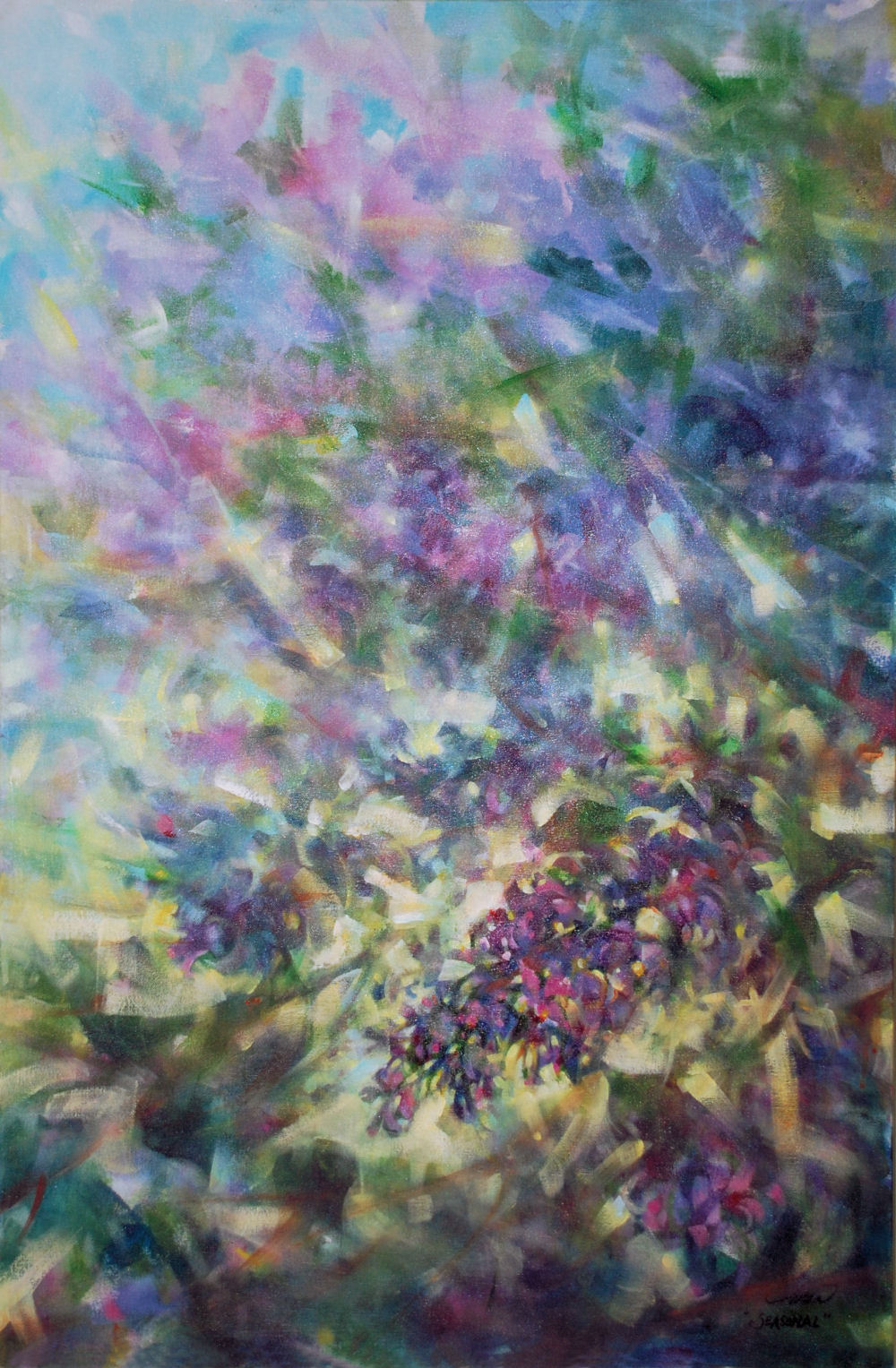

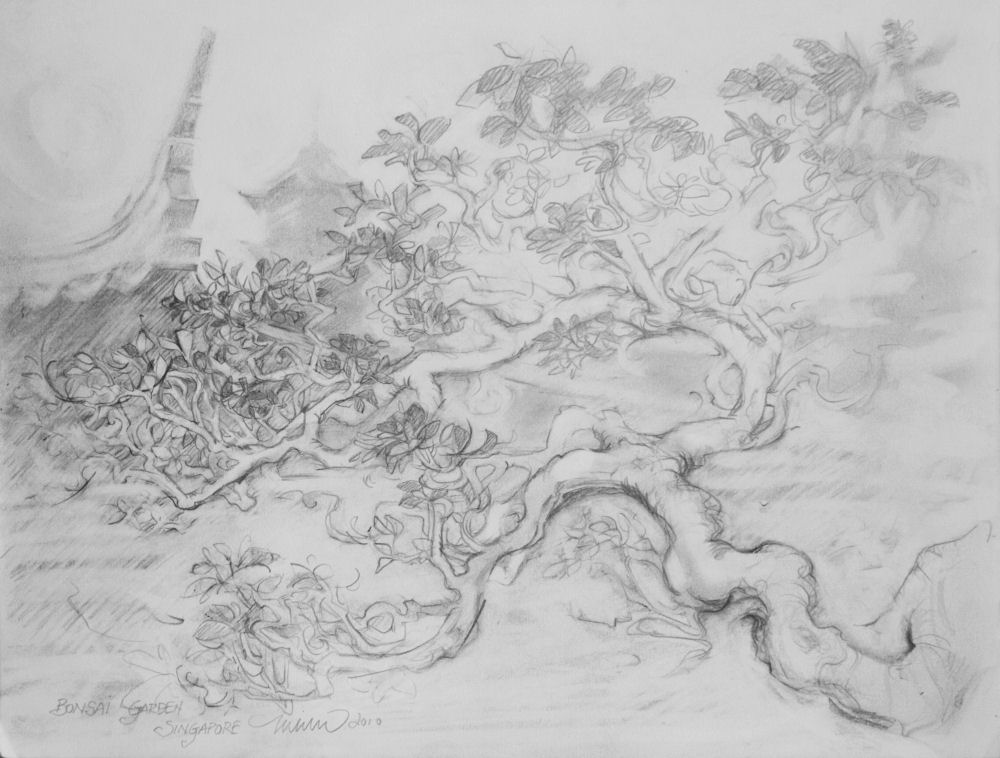

On exhibit at Oxide Gallery, Denton, TX are: Milkweed Melody, 27H x 33W inches framed Oil Pastels on WC paper, has brassy-gold frame painted with an extension of the drawing. Bonsai Garden, 12 x 15 inches graphite on paper, and Lilacs, 36 x 24 x 2 inches acrylics on canvas, gallery wrapped sides painted, narrow frame, which can be displayed horizontally or vertically.

On exhibit at Oxide Gallery, Denton, TX are: Milkweed Melody, 27H x 33W inches framed Oil Pastels on WC paper, has brassy-gold frame painted with an extension of the drawing. Bonsai Garden, 12 x 15 inches graphite on paper, and Lilacs, 36 x 24 x 2 inches acrylics on canvas, gallery wrapped sides painted, narrow frame, which can be displayed horizontally or vertically.

Toil and Peaceful Life

Wednesday, July 7th, 2010

“Art is a human activity having for its purpose the transmission to others of the highest and best feelings to which [humanity has] risen.”

Leo Tolstoy

Creating art is always a personal endeavour, and every so often I’m drawn to study only for the deeper experience of it; for the kind of education and understanding that can’t come through reading or any other means. Here is a painting I started in May, along with links and information about a unique part of Canadian history that many Canadians are not even aware of, a group of Russian immigrants who made significant contributions to, and the development of, the Canadian prairies. Next week I’ll be driving up to Alberta through Blaine Lake, Saskatchewan where some of the Doukhobors, whom I’ve just recently learned are part of my own heritage, settled during the 19th century. Upon returning from this final leg of summer travel there is another painting commission to complete, so I’ll be blogging regularly again and finishing this painting in about two months.

“Toil and Peaceful Life” (quote, Peter V. Verigin), 24 x 36 x 2 inches acrylics on canvas. Study only, NFS, work in progress: There are harsh contrasts and colors at this stage, so am planning to paint over the whole surface with my friend Virginia’s white wash formula (1/2 guesso, 1/4 matte medium and 1/4 water), then will gradually bring out details again by scrubbing areas away with a wet cloth and repainting as well. Further layers of siennas, umbers, pale yellows, unbleached titanium washes etc. will be treated the same way.

When the light bulb on my sewing machine burnt out – it won’t work without one – I could have hopped in the car and driven three blocks to go buy another, but instead made due hemming a garment by manually spinning the wheel on the machine. I had already started the above painting referring to an old photo of 16 Doukhobor women pulling and two men directing a plow as they tilled the land in southern Manitoba, Canada’s eastern-most prairie province, during the late 1800’s. This is one of the more powerful images portraying the character of the Doukhobors, who left their homeland in Russia because of religious persecution, never allowed to return, becoming the largest mass immigration in Canadian history.

When the light bulb on my sewing machine burnt out – it won’t work without one – I could have hopped in the car and driven three blocks to go buy another, but instead made due hemming a garment by manually spinning the wheel on the machine. I had already started the above painting referring to an old photo of 16 Doukhobor women pulling and two men directing a plow as they tilled the land in southern Manitoba, Canada’s eastern-most prairie province, during the late 1800’s. This is one of the more powerful images portraying the character of the Doukhobors, who left their homeland in Russia because of religious persecution, never allowed to return, becoming the largest mass immigration in Canadian history.

I’ve often wondered how it must have been for women in the past, considering all of the chores that raising a family and taking care of the home must have entailed. On top of that, there was little relief from extreme weather conditions as, for example, during the heat of summer all of these responsibilities were done wearing long dresses, petticoats and bonnets. I guess it was with this in mind that I endured impatiently sewing my jeans without electricity.

The small amount of soil I turn over in the garden is planted mostly with flowers. The few veggies that are novel to watch grow from seed to fruition are not crucual to the survival of my family. While I’m purchasing ready-wound thread on a plastic bobbin, I can select from a number of food choices and shop during any time of day, 24 hours a day in a 7 day week. Todays’ lifestyles are so far removed from the realities that pioneers in any land must have faced. Living in small communities where all could share the work as well as morally support each other made complete sense. So it was for the Doukhobors, living a philosophy very similar to the Hutterites, the Mennonites, and the Amish.

Photos are photos and paintings are paintings, but as traditional artists we can take advantage of the art of photography as inspiration to trigger motivation and memories, recreate impressions, and refer to for details. If photos are used as reference, very soon after painting begins I rely on and respond more to what’s happening on the canvas. For some time before putting brush to canvas, every detail of a subject adds to an internal mental picture, one that gradually envisions the painting finished to a certain degree. In some cases I’ll work from pictures of historic art or artifacts as educational studies, or from a client’s photo if they commission the reproduction of a favorite scene. Always though, the resulting art is an emotional translation.

The first thing that strikes me in the enlarged re-re-reproduced print I’m working from is how little the quality of the image matters. The shadows on the faces of each individual say it all. Some appear curious about having their photo taken, and most are more concerned about the task at hand. Though the image is crude by modern standards, and maybe even partly due to it, we are able to share the raw truth of a moment in one of an uncountable number of cultures throughout human history who worked so physically this way. For most of our time here on earth, we, like all of nature, knew we depended on the land, and it truly was survival of the fittest. I can only hope to capture the calibre of this story as well as the photo does.

Sometimes a painting can never be as effective as a photo, particularly when it comes to human portraits. In intances like this, there is so much value in “the journey” of your efforts. Painting such a scene, it really is like being transported. Of course the goal is to make the work successful, and artists all hope and plan for sales, but we also need to make time for creating work that feeds our soul and brings us back to the inner sources that pulled us into this not-always-externally-fulfilling vocation in the first place. When I recommend forgetting the rules and listening to your own, that’s what I mean. Even if you have never tried to paint or draw before, or you think you don’t have enough skill, you are as capable as anyone if you are spurred on by your emotions toward subjects you love, using whatever methods you enjoy.

Facebook – group intro:

“Toil and Peaceful Life”

The name Doukhobor means “spirit wrestler”. Although many of their beliefs descended from Christianity, being a Doukhobor is more of a way of life than a religion. Doukhobors are a group of pacifists that came to Canada from Russia to escape persecution for their beliefs at the end of the 19th century. The most well known leader of the Doukhobors was Peter ‘Lordly’ Verigin. The Doukhobors established communites across Western Canada, many times cultivating land that was not seen as desirable. There are still reminants of Doukhobor villages primarily in British Columbia and Saskatchewan.

“…The settlers found Saskatchewan winters much harsher than those in Transcaucasia, and were particularly disappointed that the climate was not as suitable for growing fruits and vegetables. Many of the men found it necessary to take non-farm jobs, especially in railway construction, while the women stayed behind to till the land…”

Susan Wiley Hardwick, “Russian Refuge: Religion, Migration, and Settlement on the North American Pacific Rim”. University of Chicago Press, 1993. ISBN 0-226-31610-6. 1993. Section “The Doukhobors”

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Doukhobor

The Doukhobors: 16th Century Russia to Canada, 2010

The origin of the Doukhobors is fairly dubious, but some information dates the culture back to 16th and 17th century Russia. Deeply spiritual, the “Doukho-borets”, which literally means “spirit wrestlers”, rejected common orthodox practices of organized religions and society, including the worship of icons and individual land ownership. As pacifists, their motto was “Toil and Peaceful Life”.

After refusing allegiance to Tsar Nicholas and military service, in 1895, they burnt all of their weapons in response to this. (The date, June 28th, has become a day of celebration of their humble roots.) Facing persecution for their beliefs, over 7,000 Doukhobors sought refuge in Canada starting in 1899.

The Doukhobors’ passage across the Atlantic Ocean was largely paid for by Quakers and Tolstoyans, who sympathized with their plight, and by the writer Leo Tolstoy, who arranged for the royalties from his novel Resurrection, his story Father Sergei, and some others, to go to the migration fund. He also raised money from wealthy friends. In the end, his efforts provided half of the immigration fund, about 30,000 rubles.

* Multicultural Canada http://multiculturalcanada.ca/node/48207

With sympathy from the Canadian government, for a $10 fee each adult male was intitially provided with 160 acres of “free land” on the prairies of central Canada; present day Saskatchewan and Manitoba. They were expected to live on and break the land, plant crops, and eventually apply for a patent to own it.

During 1906, a new Parliamentary Minister revised their previous agreement to laws that commanded a pledge of allegiance to the Crown or else lose their homesteads. In 1907, 2,500 homesteads were cancelled, causing communal splits into three distinct groups. The largest group of Doukhobors, incuding Peter Verigin, the man who had re-documented and defined their Orthodox faith, moved to British Columbia. The “Sons of Freedom” also went to B.C., but were radically different than the Community Doukhobors. They actively protested (sometimes nude!) issues arising from Canadian governmental control over their way of life, creating misunderstandings and negativity toward Doukhobors in general that remain to this day. The “Independents” maintained their homesteads in Saskatchewan in compliance with the new Canadian laws.

1908 to 1912: Peter Veregin’s group purchased land in the West Kootenays, B.C. and developed large communal enterprises. The Doukhobors now call themselves the Christian Community of Universal Brotherhood (CCUB), situated in Brilliant, B.C..